macOS is a rather unique operating system, one which I like a great deal. This post started as a a list of tips I wrote for a friend who’s switching to macOS, but evidently I got carried away enough to turn it into a blog post. In my opinion it’s a good idea to first understand how the system was designed to be used before decrying it as ill-conceived or making it something it isn’t using third-party window managers, app switchers, and so on. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with these things or with preferring the way other systems work, but at least give the “Mac way” a chance first! To this end I’ve prefixed the list of tips with a section on high-level ideas. Feel free to skip ahead, though!

Interaction paradigms

macOS has two fundamental interaction paradigms, one explicit and the other implicit.1

The implicit interaction paradigm consists of direct manipulation of onscreen elements by the user. For example, the user can drag a PDF document from the Desktop onto the Mail app icon in the Dock to compose a new message with that file as an attachment, drag an audio file onto the QuickTime Player icon in the App Switcher to open it, or drag some text selected in TextEdit onto Safari’s address bar to search for it. The action is implicit in the context.

The explicit interaction paradigm, on the other hand, is constructed from commands: the user is presented with a list of actions that are currently available, can browse through the list to refresh their memory, and then make a selection. For example, right-clicking selected text in TextEdit reveals a context menu containing, among other menu items, “Search With Google”, which searches for the selected text in a new browser tab when chosen. The user didn’t need to guess what would happen when they invoked the command in the same way they had to when dragging the selection onto the address bar, nor did they need to memorize that that’s something you can even do; the command was right there in front of them.

Drag and drop

macOS supports drag and drop very thoroughly. Due to spring loading, many tasks that would typically be accomplished using copy-paste can be performed more spontaneously using drag-and-drop. The attentive reader might notice that copy-paste and drag-and-drop perform the same exact function except using different paradigms: copy-paste is situated in the explicit world of menus and commands, while drag-and-drop is implicit, direct manipulation.

A favorite application of drag-and-drop of mine is open and save panels. Dragging a file into an open or save panel reveals that file in the panel, seen here combined with proxy icons:

For some ungodly reason Apple only shows proxy icons on hover since Big Sur (as you can see in the video above), so I always enable the “Show window title icons” preference in System Settings > Accessibility > Display.

Proxy icons work well with spring loading:

Menus and the menu bar

The menu bar lists every action you can take in the active app. Rather than something special unto themselves, context menus merely display the small subset of menu items immediately relevant to whatever object you right-clicked. This results in the nice property that users can explore what capabilities an app has just by browsing through the menu items in the menu bar, which is always in the same easy-to-reach place on the display and always has the same contents for a given app, no matter which of the app’s windows is focused. The default shortcut of ⇧⌘/ allows searching through menu items, while System Settings > Keyboard > Keyboard Shortcuts… > App Shortcuts lets you customize the shortcut for any menu item in any app (or across all apps if you like).

There are a small number of menu items used so infrequently by the vast majority of users that having them ever-present in menus actually does more harm than the good they do to the few people who use them once in a blue moon. macOS has “alternate” menu items as a solution to this problem: menu items which only appear while the option key is held. Try holding option whenever you have a menu on the screen! File > Close changes to Close All, Window > Bring All to Front changes to Arrange in Front, and so on. One particularly useful one is how Edit > Copy “Holiday Pictures” in Finder changes to Copy “Holiday Pictures” as Pathname. Note that all these work just as well in context menus as in the menus accessible from the menu bar.

Apps over windows

Something that often trips up people new to macOS is that the system is application-oriented rather than window-oriented (as Windows is): on macOS apps “contain” their windows, while on Windows an app’s windows are the app. This single difference in philosophy explains why the Windows taskbar lists open windows (or at least used to), while the Mac’s Dock lists apps, which in turn list their windows when right-clicked. It’s also why the App Switcher (⌘⇥) lists apps, while Windows’ Task Switcher (Alt+Tab) lists windows.

A frequent source of confusion for new Mac users is how apps don’t quit when you close their last window – when you close the last Safari window you still see “Safari” in the menu bar which only vanishes if you quit the app entirely. Though we now know why this is the case on a philosophical level, what’s the reason practically? Keep in mind that the menu bar is a central place listing every command available to the user: even with no windows open, having access to an app’s menu bar is still a useful thing! The menu bar provides access to the entirety of an app’s functionality, window or no window.

Documents

Documents are a fundamental part of the operating system. Recently-opened documents appear in File > Open Recent, as well as in the Apple menu under Recent Items. Recent documents also appear in the Dock menu of every app, as well as in App Exposé. Apps can provide rich thumbnails and interactive previews for their files, both of which appear across the system from Finder to Spotlight to Quick Look.

Around a decade ago Apple decided to revamp macOS’s document model: since OS X Lion, what you see in a document window is what’s on disk (as far as the user is concerned anyway). In other words, autosave. The Save menu item doesn’t only force an autosave, either – it also adds a new version of the document to the versions database (!). You can browse previous versions of any document in a Time Machine-like interface using the Browse All Versions… menu item. Closing an edited document doesn’t confirm if you want to save your changes, either. Instead, the next time you open the document it’ll still have all your changes, and if necessary you can revert to the last saved version using Edit > Revert To… > Last Saved. It’s worth mentioning, too, that Save As… was replaced by Duplicate & Rename…, and that this is in fact a good thing. (Save As… is still available as an alternate menu item, though I’m not sure why you’d want to use it.)

One thing that I found quite surprising is how Apple views file extensions as a historical relic supported by macOS only for compatibility reasons. The filesystem stores a “hide extension” bit for each file indicating whether the system should hide the file’s extension in user interfaces, and all the built-in apps set this bit for the user-visible files they create. For many years I was unaware of this behavior and just enabled the “Show all filename extensions” checkbox in Finder settings, thinking that hiding file extensions was some sort of paternalistic simplification. Instead, I now appreciate the design: if you think about it, file extensions really are quite primitive, no? Finder shows me a nice human-readable “Kind” column if I ask it to, anyway, and foreign files downloaded from the internet don’t have the “hide extension” bit set, avoiding potential confusion with unfamiliar formats while omitting extensions for the files I work with regularly.

Window management

Windows and Linux users often swear by window tiling features, saying that macOS’s window management isn’t up to scratch. I contend that this is actually a difference in philosophy.

As I mentioned in the last section, macOS is a document-focused operating system, and users are encouraged to believe that windows are documents. It makes little sense to tile many sorts of documents – anything graphical, really, like websites, images, page layouts, and so on. Instead, I think you’d want to resize the window to suit the inherent dimensions of the content. What use is tiling if you end up cutting a PDF off halfway down a page just because you want it to take up exactly a quarter of your screen?

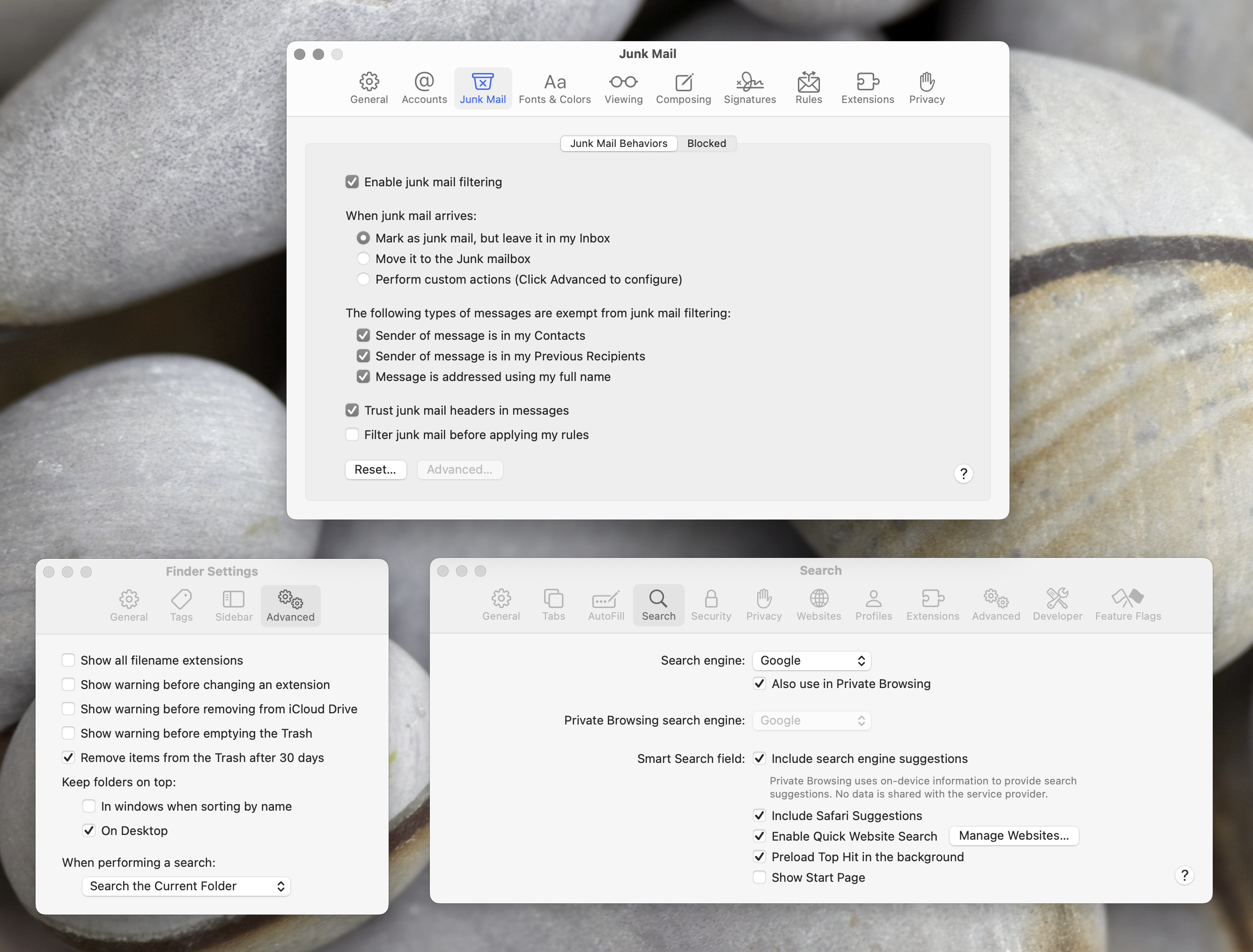

On top of that, most macOS interfaces tend to avoid scrolling content, instead preferring to arrange controls carefully and sizing the window to fit around them. This is especially evident in settings windows (ignoring the horror that is System Settings):

I’d argue that the “Mac way” to manage your windows isn’t to maximize everything or tile your windows into perfect halves and quarters.2 Instead, fit your windows to their content automatically by “zooming” them:

As you can see, repeated invocations of the menu item toggle between the zoomed and original window size & position. You can also zoom a window by option-clicking the third traffic light button (the full screen arrows will turn into a plus sign) or by double-clicking its titlebar:

Sadly, few applications take the time to customize the zoomed size of their windows, so many people are led to believe that “zoom” is just a “maximize” that doesn’t work in Safari, Finder and Preview, or something.

The end result of this is that you don’t really “manage” windows, per se. Instead, windows pile up on the screen like sheets of paper on a desktop, and it somehow works out fine (at least for me).3 macOS has several special kinds of window which help keep things in check. Panels, small utility windows for a particular task, disappear automatically when the app which created them is inactive:

Popovers are another kind of small window for a particular task. These are attached to a certain point in a parent window and close automatically when they are no longer needed:

Finally, sheets are modal dialogs attached to the window they came from. This reduces clutter while also making it obvious why a window isn’t responding to inputs (it has a sheet over it!).

Processes

Traditionally, if an app is open on your computer then there’s a process running which corresponds to that app, and if an app is closed then there’s no process. On macOS it’s possible for an app which ostensibly is running to not have a process, and vice versa.

The operating system will sometimes ask a running app to save its user interface state to disk and terminate, after which all its windows are replaced with screenshots. Yes, really. Its indicator light in the Dock will still shine, and the app still appears in the App Switcher. When the user next tries to interact with the app its process is launched once more, it’ll restore its user interface to look just like it did before it terminated, and the screenshots get replaced by live windows.

It also goes the other way: after all an app’s windows have closed and the user switches to something else, the app will appear to quit, when in reality macOS will keep the process around for a while in case the user “relaunches” the app.4

This feature is named Automatic Termination. Not as many apps adopt it as I’d like, but it’s still pretty cool to know that it’s there. In general, I’d suggest you stop quitting apps manually and instead allow the operating system to manage the app lifecycle, if only because it’s soooo coooooool that it REPLACES YOUR WINDOWS WITH SCREENSHOTS! I just like it for some inexplicable reason. Maybe it reduces cognitive load, just a bit? Turning off the running app indicator lights in the Dock helped me get used to this, for what it’s worth.

There’s an alternate menu item named Quit and Keep Windows with the keyboard shortcut ⌥⌘Q which, as the name suggests, restores an app’s open windows the next time it’s opened using the same codepath as Automatic Termination’s window restoration. You can swap ⌘Q and ⌥⌘Q by disabling the “Close windows when quitting an application” preference under System Settings > Desktop & Dock. I’m a big fan of this as it lets me not think twice about quitting apps, and need to take the deliberate action of invoking Quit and Close All Windows with ⌥⌘Q when I really want all an app’s windows gone.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t link to John Siracusa’s treatment of this topic.

Assorted tips

There’s an endless number of little random tricks, too. I could probably list them forever, but thankfully I don’t have to: the internet is utterly chock full of macOS tips videos and listicles. For what it’s worth, I have fond memories of watching macOS tricks videos by Snazzy Labs on YouTube when I was younger.

Here’s a couple of my favorites, anyway:

Use File > Quick Look (⌘Y) in Finder to open a preview for the selected items. (Pressing the spacebar works too!)

Menus appear on mouse-down so you can select menu items by depressing the right mouse button, sweeping down through the menu to your desired menu item, then releasing the mouse button.

Apps can be hidden using [Current App] > Hide [Current App], or ⌘H. This makes all the app’s windows disappear instantly until you activate the app again by clicking it in the Dock or selecting it from the App Switcher. I much prefer this to minimizing. Hide Others (⌥⌘H) hides all apps apart from the active one, which is quite useful when you have a bunch of clutter on the screen and want to focus. You can unhide all the other apps again in one go using the Show All menu item.

Hold command while clicking in an unfocused window to send it mouse events without focusing it. Hold option while clicking in it to hide the current app and switch to that window in one go (I use that one a bunch!).

As you’re tabbing through apps in the App Switcher, keep holding down command and hit Q to quit the currently selected app, or hit H to hide it. The App Switcher remains open so you can triage open apps quickly.

Run defaults write com.apple.dock showhidden -bool YES && killall Dock

to dim hidden apps in the Dock.

Holding option while resizing a window vertically or horizontally resizes across the axis; resizing diagonally with option resizes from all sides; holding shift constrains to aspect ratio; shift and option can be combined. This also works for resizing all kinds of rectangles throughout the system, e.g. in Preview, Pages and Screenshot (which is accessible from anywhere using ⇧⌘5).

Right-clicking the proxy icon or document name in a window’s titlebar reveals a context menu showing the document’s parent folders. Select the immediate parent to reveal the document in Finder.

Also, I highly recommend getting to know Preview well. Reordering pages in a PDF (drag and drop!), concatenating PDFs (also drag and drop!), adding annotations and signatures, cropping PDFs and images, resizing images, changing formats, etc come up quite often, so it’s handy to have a solid app for those things built-in.

If you’d like more tips, I can recommend this exhaustive list. It has some really obscure ones I guarantee you haven’t heard of.

This categorization comes from an old version of the Human Interface Guidelines. ↩︎

That said, I do use the newly-added built-in window tiling for putting a code editor and a browser side-by-side when I don’t have an external monitor connected to my laptop, but only because screen space is at a premium and the resulting aspect ratios fit the content quite well, anyway. Tiling things like Messages, Finder or settings windows isn’t my cup of tea. ↩︎

You can heighten the illusion by running

defaults write -g NSWindowShouldDragOnGesture -bool YESthen logging out and logging back in again (which isn’t a big deal with state restoration!). This lets you move a window by dragging it from anywhere while holding the control and command keys. ↩︎

In all my years of using macOS I’d never seen this behavior, so when I first heard about it I assumed Apple must’ve removed it at some point. Nope! It turns out that some (but not all) apps which request accessibility permissions can disturb this aspect of Automatic Termination from working (perhaps accessibility permissions require stable access to the list of open apps, or something?). Try removing accessibility permissions from all your apps and then see if you can replicate the behavior I described in, say, Preview, Pages or QuickTime Player. ↩︎

Luna Razzaghipour

15 November 2024